Paperslip Co-Founder’s Ongoing Push for Recognition of Systemic Switching — Since 2018.

Posted to Paperslip on September 12th, 2025.

Download PDF:

The Rejected 2019 Proposal To Discuss Systemic Switching At IKAA 2019 — By Paperslip’s Co-Founder.

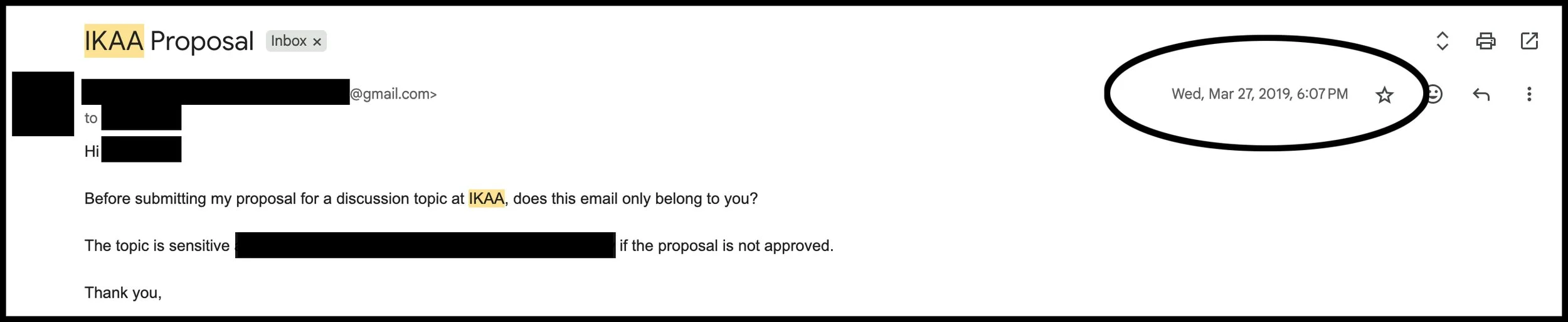

*This proposal was submitted to IKAA on March 27th, 2019.

*Please note that I have redacted some sensitive information.

*Please see the excerpted “Proposed Session” below this section, which is easier to read than the PDF.

+

Preface:

I’m sharing my original 2019 IKAA proposal here for the first time. It has never been published online—until now. I believe this document not only sheds light on the early days of the TRC movement, but also affirms that switching would not have been recognized as a human rights violation in the TRC’s March 26th, 2025 Interim Report without the critical—yet unacknowledged—groundwork I have been laying not only into the topic of switching, but into KSS practices overall since 2018.

On March 26th, 2025, South Korea’s Second Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC 2) formally recognized switching as a human rights violation, and more or less used the exact definition of switching which I had personally codified since 2018 in its Interim Report. Ironically, my IKAA proposal, which I submitted on March 27th, 2019, came nearly exactly 6 years to the day before the TRC 2 Interim Report of March 26th, 2025 formally acknowledged switching as a human rights violation.

Here is what I wrote in my March 27th, 2019 session proposal to IKAA:

”To my shock, I almost immediately found KADs (Korean Adoptees) whose files had been switched with orphans who had died, were picked up by birth parents prior to their adoptions, or were too sickly to travel.”

Here is what the TRC 2 Interim Report of March 26th, 2025 said about switching:

”The Commission confirmed the following specific human rights violations in the intercountry adoption process (see the attached documents for details)…

…Deliberate Identity Substitution: If a child in the adoption process passed away or was reclaimed by their biological family, agencies would substitute another child’s identity to expedite the adoption, severely violating adoptees’ rights to their true identities”

The similarity between the definition of switching that I codified in 2018 and the one used by the TRC 2 is neither accidental nor coincidental. On December 20th, 2020—two years before the formal TRC 2 Investigation into Overseas Adoption began on December 9th, 2022—I compiled and submitted a summary of approximately a dozen cases involving switched Adoptees to the head of the TRC through a personal contact. In the preface to that submission, I included the definition of switching as I had articulated it in 2018. I’m pleased to see that this definition has been reflected in the TRC 2 Interim Report dated March 26th, 2025.

The story of how switching came to be acknowledged as a human rights violation by TRC 2 is a long and complicated one, and at its heart is my personal investigation into my own switch case and the separate switch case of my deceased twin sister, whose file I only discovered by accident at my Korean Adoption Agency in 2019. This story involves the wholesale erasure of credit for my years long efforts by the Danish Korean Rights Group (DKRG), whose remaining leadership continues to shamelessly and ruthlessly take credit for not only my work, but the work of many others.

In addition to the years of aggravation caused by DKRG, securing permission to speak about switching at U.S. Korean Adoptee conferences has been a grueling, uphill battle. My 2019 proposal to discuss systemic switching was almost immediately rejected by IKAA (International Korean Adoptee Associations). Years later, in 2024, KAAN (Korean Adoptee Adoptive Family Network) also rejected my proposal to discuss the (then) upcoming FRONTLINE documentary “South Korea’s Adoption Reckoning,” systemic switching, and the impending transfer of all Korean Adoption Agency files to the Korean Government Agency NCRC (National Center for the Rights of the Child). It wasn’t until after the documentary aired — a major project for which my case was ground zero, and for which I received zero credit — that KAAN finally accepted my 2025 proposal to present. That presentation focused on my switch case and how it contributed both to the TRC 2 Investigation into Overseas Adoption and the development of the FRONTLINE documentary.

Ironically, in order to even be allowed to present at Korean Adoption conferences, I had to spend years helping to reshape the entire conversation around adoption from South Korea. While I would never claim credit for the decades of tireless work of countless Korean Adoptee activists worldwide, few people realize that my investigation into my and my twin’s separate switch cases became the catalyst—not only for the founding of Paperslip in 2020, but also for the 2024 FRONTLINE/AP documentary, South Korea’s Adoption Reckoning and related AP articles, the TRC 2 Investigation into Overseas Adoption of 2022-2025, and the TRC 2’s March 26th, 2025 recognition of switching as a human rights violation.

To trace the roots of this story, we have to go back to 2018.

In 2018, during my first trip to Korea as an adult, I discovered that I had been switched. In 2019, during my second visit to Korea, I submitted a proposal to the International Korean Adoptee Associations (IKAA) conference, aiming to speak publicly about the systemic nature of switching, which I had only just begun uncovering. By then, I had already connected with other switched Korean Adoptees—many of them in Denmark, one of the primary countries to which my Korean Adoption Agency, Korea Social Service (KSS), sent children between 1964 and 2012.

In the summer of 2018, shortly after relocating from the U.S. to Florence, Italy, to study art, I organized a meeting in Denmark with three Danish KSS Adoptees who had also discovered they were switched. Ironically, as the only American among them, I was the one who brought them together—they hadn’t previously known of one another's cases. My collaboration with them provided key insights that deepened my investigation into the systemic nature of switching.

Over time, I documented their stories—alongside more than a dozen other switched Adoptee cases—and submitted them informally to the head of South Korea’s Second Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) on December 18th, 2020, through a contact who knew the head of the TRC. The TRC had only been reestablished eight days earlier, on December 10th, 2020, and at the time, was not planning to include Adoptee cases in its investigations. I thus became the first person in history to submit any cases of Korean Adoptees to the TRC. While these efforts did not trigger a formal investigation, they did lay the groundwork for the later official effort by the TRC 2 to investigate Overseas Adoption. Perhaps not coincidentally, these efforts were witnessed by DKRG’s Boonyoung Han, at a time when DKRG had not even yet been formed.

Later, many of the switched Adoptees I had organized—including myself and all three of the switched Danish KSS Adoptees I had met with in September 2018—formally submitted our cases to the TRC’s official Investigation into Overseas Adoption, which did not begin until December 9th, 2022. However, due to ongoing mistreatment and abuse by DKRG leaders Peter Møller and Boonyoung Han, I chose to withdraw my TRC 2 case in March 2023. In hindsight, this was deeply unfortunate: my case was among the first 34 accepted by the TRC for investigation, and given the strength of the documentary evidence, which is rare for Adoptees, it likely would have resulted in a favorable judgment. It’s ironic as DKRG later struggled to collect enough useful evidence from Adoptees. Ultimately, 311 of the original 357 cases submitted to the TRC 2 were suspended, many for lack of evidence. Only 56 cases received judgments by TRC 2—and only those 56 Adoptees who received judgments are eligible to sue the Korean Government for damages. Thus DKRG not only cost me a chance at justice for myself and my deceased twin sister, but also the chance to sue for reparations.

It is no coincidence that TRC 2 ultimately recognized switching as a human rights violation — this outcome is a direct result of the work I began in 2018, identifying and organizing switched Adoptees with the express purpose of bringing our cases to the attention of the TRC and the press — both goals of which have now been accomplished.

+

Unfortunately, back in 2019, my proposal to make a presentation about switching at IKAA was quickly rejected by the Korean Adoptees leading the organization. IKAA—one of the largest and most influential Korean Adoptee networks in the world—is an incredible community, but its longstanding ties to financial sponsors in Korea have significantly shaped its programming and priorities, often sidelining and suppressing critical perspectives on adoption. IKAA holds a conference in Seoul every three years for Adoptees, but it wasn’t until 2023 that I was finally allowed to present at the conference—screening the SBS (Seoul Broadcasting System) documentary about my case, which was released on December 24th, 2022. Even then, getting the screening approved was a struggle. IKAA initially proposed that attendees simply watch the documentary online, and it was only through the support of an Adoptee contact with closer ties to IKAA that the film was ultimately screened at the conference.

It wouldn’t be until December 24th, 2022, that systemic switching in Korean Adoption was publicly acknowledged anywhere in the world—when the hour long documentary about my switch case aired on SBS in South Korea. Though individual switch cases had occasionally been reported over the years, this was the first time systemic switching had been addressed in Korean media—or any international media at all—especially in such a prominent outlet. SBS did a phenomenal job on the documentary, and it was a huge privilege to work with them. I am forever grateful for their huge commitment and dedication. However, to suit Korean tastes, the documentary presented a much prettier version of my story, and many aspects of my twin’s switch case could not be discussed due to confidentiality.

In 2019, during the course of investigating my own switch case, I unknowingly uncovered what I would later realize (in 2020) was the switch file of my twin sister, who likely died at KSS in 1975. My investigation into my and my twin’s separate switch cases became the basis for my co-founding Paperslip in January 2020.

In August 2022, I was approached by Peter Møller of the newly formed Danish Korean Rights Group (DKRG), which had only formed in April or May of that year—years after I first discovered systemic switching. Moeller asked me to help spread the word among U.S. Adoptees about the TRC’s upcoming investigation into Overseas Adoption. I agreed wholeheartedly. However, on December 7th, 2022—just days before the SBS documentary aired, and right as the TRC investigation into Overseas Adoption was formally launching—DKRG blocked me from the movement without explanation. To this day, they have never provided any explanation or apology. DKRG’s Peter Møller and Boonyoung Han, the latter of whom had directly witnessed but not contributed to my research into switching and KSS for years, then went to the press about switching, the systemic nature of which I had been researching for years. Egregiously, neither my work nor Paperslip has ever been mentioned by DKRG in the press, despite their purported commitment to “Truth” and “Korean Adoptee Rights”. Unfortunately, I did not know enough about the personalities of these two individuals to understand that I never should have worked with them in the first place.

Boonyoung Han, Peter Møller’s wife and fellow DKRG member, had long been an invited observer of my investigation into KSS practice and systemic switching. Yet, she and Moeller later attempted to co-opt credit for major portions of my work, disregarding not only my contributions but those of many others as well. Today, they egregiously falsely assert that they are the only two founders of DKRG, despite the fact that there were five other co-founders who have since been pushed out.

As mentioned at the beginning:

I’m sharing my original 2019 IKAA proposal here for the first time. It has never been published online—until now. I believe this document not only sheds light on the early days of the TRC movement, but also affirms that switching would not have been recognized as a human rights violation in the TRC’s March 26th, 2025 Interim Report without the critical—yet unacknowledged—groundwork I have been laying not only into switching, but into KSS practices overall since 2018.

+

Below: Excerpt From

The Rejected 2019 Proposal To Discuss Systemic Switching At IKAA 2019 — By Paperslip’s Co-Founder.

*Below is my verbatim 2019 Session Proposal to IKAA. It was rejected after submission. I would not be allowed to make a presentation about switching (through a screening of the SBS documentary about my case) at IKAA until 2023.

*Please note that I have redacted some sensitive information.

*Bolds and red highlighting + new notes mine on September 12th, 2025.

*Please download the PDF of the entire proposal above.

+

“(Redacted) Bio:

Korean American Adoptee (redacted) is an artist who has a decade of college level teaching experience who has recently returned to school in Florence, Italy to hone her artistic skills to a higher degree. Prior to her relocation to Florence, (redacted) lived in Los Angeles, where she founded her own art studio, (redacted) which she ran for 7 years. She originally grew up on the East Coast of the US and has studied art across the US and now in Europe. She recently discovered the international KAD community and has enjoyed connecting with fellow adoptees with diverse backgrounds and personal histories. This is her first IKAA, and only her third trip to Korea.

Detail of your proposed session (500 words total maximum). (Please detail your motive(s), objective(s), and intended outcome(s) in the below headings).

Motive/Rationale:

My topic is baby switching in Korean adoption, specifically concerning my own case of switched identity. I grew up believing that the information in my adoption file from Korean Social Service (KSS) was my own. However, upon returning from a trip to Korea in Summer 2018 as part of the Mosaic Tour, and visiting my adoption agency and tracing the steps of the girl I believed to be me, I began to investigate long held suspicions that the baby in the photo originally provided to my adoptive parents prior to my adoption was not actually me. Over the course of time last Summer, my suspicions were supported by translations of "my” original adoption documents, which turned out to contain 6 pages I had never seen with reference to another girl - the girl I believe was actually "me". A famed Dysmorphologist (or doctor who studies the facial changes of children) confirmed that based on the differing ear structures between the real me and the baby in the KSS photo I had grown up believing to be me, the baby in the photo was not me. At this point I reached out to the international KAD community online, suspecting at most that my photo had accidentally been switched with that of another living orphan. To my shock, I almost immediately found KADs whose files had been switched with orphans who had died, were picked up by birth parents prior to their adoptions, or were too sickly to travel. (Note on September 12th, 2025: Please note that my definition of switching was used almost verbatim in the TRC 2 Interim Report of March 25th, 2025, which officially acknowledged switching as a human rights violation). At this point, my concept of my identity exploded and since that time, I have been trying to gain access to what I believe to be my real file at KSS. Ironically, I have a photo of the box containing what I believe to me my real file, whose number was referenced in the back of what I now believe to be the file of an orphan that may have died prior to my being sent to the US to my adoptive parents in her place. While I do not have definitive proof that I was switched, my adoptive parents believe my suspicions are substantiated by many inconsistencies both in my file and in emails from my KSS social worker, who has not been forthcoming with the truth. I currently have (redacted) in Korea attempting to obtain access to the file on the real me via KAS. Email communication from my social worker at KSS, who (redacted) was reluctant to let me photograph what I thought were my innocuous adoption files during my visit last Summer, has only served to strengthen the suspicions of myself and my adoptive parents that there is information that is being hidden. This real file, should it exist, may or may not contain birth parent information.

Ironically, the (redacted) I believed up until last Summer to be mine, (redacted).

Objective(s)/Purpose(s):

I now am connected to multiple switched KADs and other supporters within the KAD community, and I think this issue needs to have more light shed upon it. I am sure there are countless more switched KADs out there who have no idea, may never have any idea, and may not want to have any idea that they may have also been switched at birth. Apart from Deann Borshay Liem's excellent "In The Matter of Cha Jung Hee", there is scant discussion or documentation that I can find of baby switching with respect to Korean adoption. I suspect that it may continue today, but have no proof that such practices still exist.

I was personally shocked and devastated by my discoveries following my trip to Korea (the first as an adult, and only the second trip to Korea in my lifetime). However, I have a ripping story to tell and I believe that many Adoptees deserve to know the truth - that such practices at least did exist in the past.

(Redacted). So I have reservations about making such a presentation, but I feel that Korean Adoptees deserve to know that these dark possibilities exist for many of us regarding our pasts.

Outcomes:

I hope that people come away from this presentation with a greater awareness of the complex realities of Korean Adoption, and begin a dialogue regarding baby switching in Korean Adoption. I myself had never heard of switching before last Summer, and my investigation and research into this topic has opened a door of understanding into the past, concerning both Korea and myself, that I had previously been unwilling to delve into. I am oddly grateful for the experience of exploring this dark piece of my past, even though its revelation has cost me time, emotional turmoil and money to investigate. Opening a door into my past as a Korean Adoptee has been on the one hand agonizing, but on the other hand has brought into my life many meaningful friendships and a deepened understanding of who I am in the context of Korean Adoption history and in the history of Korea itself.

I also hope that people gain from this presentation a sense of compassion for the choices Korean women and families (many of them newly minted industrial workers) made during a time following the destruction of the Korean War. I myself never grew up with any knowledge of Korean War history, and there were no factual possibilities to fill in the blanks between the twin "P" Korean Adoptee fantasies of being born either a Princess or of a Prostitute. I don't absolve KSS and other similar agencies for casting aside our real identities as though they had no value, but I also want to discuss my (redacted) communications. However, because KSS and other agencies seemed to have routinely switched babies without regard for our real identities, I may never know if I was even a "legitimate" orphan, or if my real file, assuming it exists, contains birth parent information. Lingering doubts are the constant companions of Korean Adoptees. Even if I one day gain access to my real file, it may or may not contain information on birth parents, who may or may not still be alive. I may never know the answers to these questions, and I am often asked by those who know my story if I wish that I had never found out. While I would not wish this condition of endless doubt on others, I am fascinated by the complexities of the past with respect to our adoptions and its repercussions for our current sense of identity.

My expectation is that in exploring these complex thoughts and feelings, others may be able to relate to and come to terms with what may very well be a permanent state of not knowing. The hope is that opening a dialogue surrounding this painful subject will prove fruitful in spreading awareness about a topic which very much needs to be discussed.

Session description (max. 100 words) for posting on IKAA Gathering 2019 marketing materials:

Korean American Adoptee (redacted) discusses her experiences of coming to terms with the fact that she may very well have been switched at birth with another orphan. Following an Adoptee Tour to Korea in Summer 2018,(redacted) learned that a long held suspicion about her adoption files had a much darker explanation than she was prepared to find out. Having always considered herself a (redacted), she was unprepared to learn that the information in her adoption file may not be at all what it seemed.”